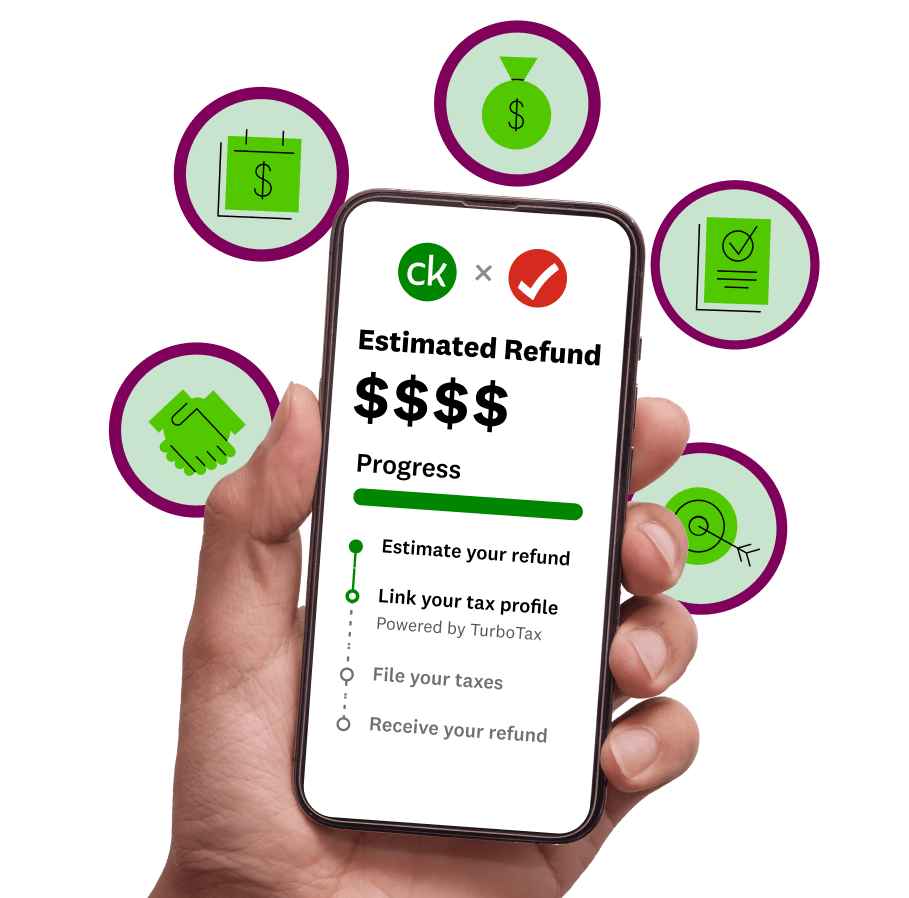

Credit Karma & TurboTax: Maximizing refunds to champion financial progress for members.

Credit Karma & TurboTax are teaming up to help you get your maximum refund fast so you can start moving toward your financial goals even faster.

Image: Tax-hero

Image: Tax-hero Image: Tax-MaxRefund

Image: Tax-MaxRefundGet your max refund, guaranteed1, or your money back.

From student loan interest to property taxes, get every deduction, every tax break, and every dollar you qualify for when you file on Credit Karma, powered by TurboTax.

Tap into fast cash.

Start working on your financial goals even sooner this year.

Image: Tax-5DE

Image: Tax-5DEUp to 5 days early

Get access to your refund up to five days early2 when you deposit it into your Credit Karma MoneyTM Spend account.3

Image: Tax-RAD

Image: Tax-RADRefund Advance

Get up to $4,0004 in as little as 60 seconds from IRS acceptance. $0 loan fees and 0% APR. Terms apply. Subject to approval.

Tax experts matched to your unique tax situation.

Whether you need an Expert Review6 just before you file, guidance from start to finish, or year-round support beyond tax season, there’s a certified TurboTax expert ready to help.7

Image: Tax-Experts

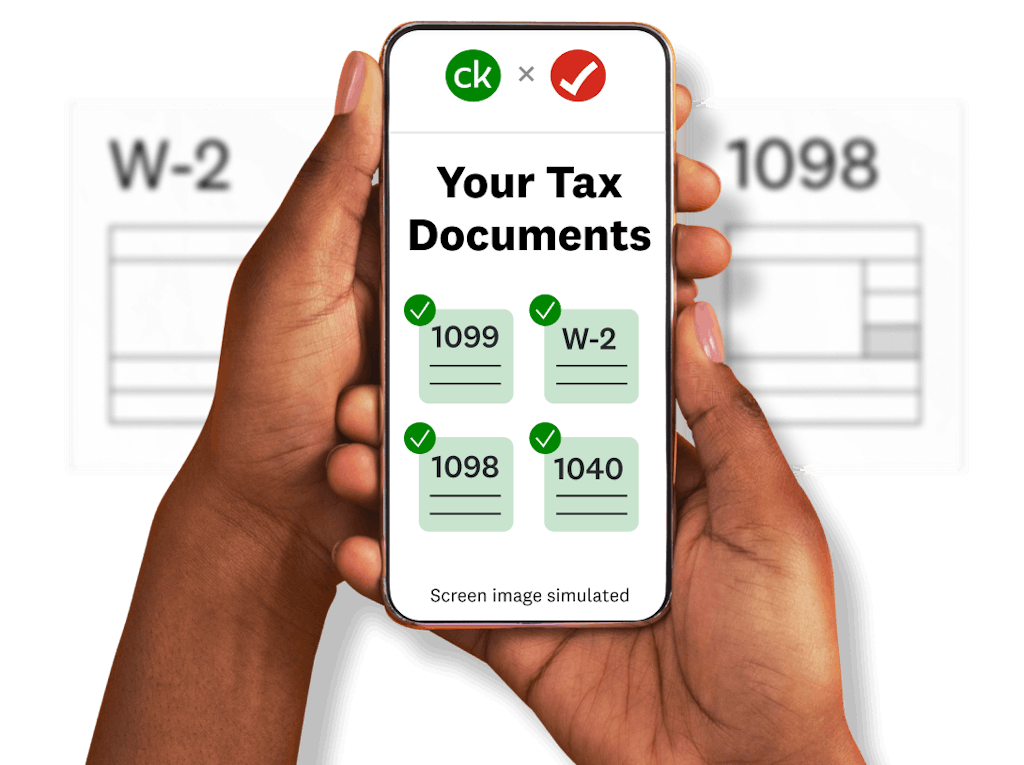

Image: Tax-Experts Image: Tax-Docs

Image: Tax-DocsUpload tax forms with a tap.

Turbocharge the filing process by using your phone to upload your tax forms. Simply snap a quick pic of your forms, verify your data, and we can help you fill in part of your tax return.5

More helpful tax tips from our editors:

Image: Tax-Icon-Editorial-1

Image: Tax-Icon-Editorial-1 Image: Tax-Icon-Editorial-2

Image: Tax-Icon-Editorial-2 Image: Tax-Icon-Editorial-3

Image: Tax-Icon-Editorial-3 Image: Tax-Icon-Editorial-4

Image: Tax-Icon-Editorial-4 Image: Tax-Icon-Editorial-5

Image: Tax-Icon-Editorial-5 Image: Tax-Icon-Editorial-6

Image: Tax-Icon-Editorial-6The capital gains tax rate: How it’s different than tax on other income

Image: Tax-Icon-Editorial-7

Image: Tax-Icon-Editorial-7Try these tips to go from a “tax season” mindset to a “tax year” approach

1If you get a larger refund or smaller tax due from another tax preparation method by filing an amended return, we’ll refund the applicable TurboTax federal and/or state purchase price paid. (TurboTax Free Edition customers are entitled to payment of $30.) This guarantee is good for the lifetime of your individual tax return, which Intuit defines as seven years from the date you filed it with TurboTax, or until December 15, 2025 for your 2024 business tax return. Additional terms and limitations apply. See Terms of Service for details.

2To be eligible, you don’t need to file your taxes with a particular tax prep service. However, you will not be eligible if you choose to pay your tax preparation fee using your federal tax refund or choose to take a Refund Advance loan. 5-day early program may change or discontinue at any time. Up to 5 days early access to your federal tax refund is compared to standard tax refund electronic deposit and is dependent on and subject to IRS submitting refund information to the bank before release date. IRS may not submit refund information early.

3Credit Karma is not a bank. Banking services provided by MVB Bank, Inc., Member FDIC. Maximum balance and transfer limits apply.

4If you expect to receive a federal refund of $500 or more, you could be eligible for a Refund Advance loan. Refund Advance loans may be issued by First Century Bank, N.A. or WebBank, neither of which are affiliated with MVB Bank, Inc., Member FDIC. Refund Advance is a loan based upon your anticipated refund and is not the refund itself. 0% APR and $0 loan fees. Availability of the Refund Advance is subject to satisfaction of identity verification, certain security requirements, eligibility criteria, and underwriting standards. This Refund Advance offer expires on April 15, 2025, or the date that available funds have been exhausted, whichever comes first. Offer exclusive to Credit Karma members only between March 1, 2025 and April 15, 2025. Offer, eligibility, and availability subject to change without further notice.

Refund Advance loans issued by First Century Bank, N.A. are facilitated by Intuit TT Offerings Inc. (NMLS # 1889291), a subsidiary of Intuit Inc. Refund Advance loans issued by WebBank are facilitated by Intuit Financing Inc. (NMLS # 1136148), a subsidiary of Intuit Inc. Although there are no loan fees associated with the Refund Advance loan, separate fees may apply if you choose to pay for TurboTax with your federal refund. Paying with your federal refund is not required for the Refund Advance loan. Additional fees may apply for other products and services that you choose.

You will not be eligible for the loan if: (1) your physical address is not included on your federal tax return, (2) your physical address is located outside of the United States or a US territory, is a PO box or is a prison address, (3) your physical address is in one of the following states: IL, CT, or NC, (4) you are less than 18 years old, (5) the tax return filed is on behalf of a deceased person, (6) you are filing certain IRS Forms (1310, 4852, 4684, 4868, 1040SS, 1040PR, 1040X, 8888, or 8862), (7) your expected refund amount is less than $500, or (8) you did not receive Forms W-2 or 1099-R or you are not reporting income on Sched C. Additional requirements: You must (a) be a Credit Karma member, (b) e-file your federal tax return with TurboTax and (c) currently have or open a Credit Karma Money™ Spend (checking) account with MVB Bank, Inc., Member FDIC. Maximum balance and transfer limits apply. Opening a Credit Karma Money™ Spend (checking) account is subject to eligibility. Please see Credit Karma Money Spend Account Terms and Disclosures for details.

Not all consumers will qualify for a loan or for the maximum loan amount. If approved, your loan will be for one of ten amounts: $250, $500, $750, $1,000, $1,500, $2,000, $2,500, $3,000, $3,500, or $4,000. Your loan amount will be based on your anticipated federal refund up to a maximum of 50% of that refund amount. Certain TurboTax Live customers who are also Credit Karma members may be eligible for a loan, issued by WebBank, in an amount that is based on the full amount of their anticipated federal refund with a maximum loan amount of $10,000, and such loans are available in amounts that are multiples of $250. Full Refund Amount calculation based upon the estimated amount of your refund less any fees associated with additional refund products. You will not receive a final decision of whether you are approved for the loan until after the IRS accepts your e-filed federal tax return. Loan repayment is deducted from your federal tax refund and reduces the subsequent refund amount paid directly to you.

If approved, your Refund Advance will be deposited into your Credit Karma Money™ Spend (checking) account shortly after the IRS accepts your e-filed federal tax return, and you may access your funds online through a virtual card. Your physical Credit Karma Visa Debit Card should arrive in 7 – 14 days. The Credit Karma Visa Debit Card is issued by MVB Bank, Inc., Member FDIC pursuant to a license from Visa U.S.A. Inc.; Visa terms and conditions apply. Other fees may apply. For more information, please visit: https://support.creditkarma.com/s/article/Are-there-fees-with-a-Credit-Karma-Money-Spend-account.

If you are approved for a loan, your tax refund after deducting the amount of your loan and agreed-upon fees (if applicable) will be placed in your Credit Karma Money™ Spend (checking) account. Tax refund funds are disbursed by the IRS, typically within 21 days of e-file acceptance. If you apply for a loan and are not approved after the IRS accepts your e-filed federal tax return, your tax refund minus any agreed-upon fees (if applicable) will be placed in your Credit Karma Money™ Spend (checking) account.

If your tax refund amounts are insufficient to pay what you owe on your loan, you will not be required to repay any remaining balance. However, you may be contacted to remind you of the remaining balance and provide payment instructions to you if you choose to repay that balance. If your loan is not paid in full, you will not be eligible to receive a Refund Advance loan in the future.

5 With streamlined TurboTax experience for CK members. May not be available for all members.

6 TurboTax Live – Tax Advice and Expert Review: Access to an expert for tax questions and Expert Review (the ability to have a tax expert review) is included with TurboTax Live Assisted or as an upgrade from another TurboTax product, and available through December 31, 2025. Access to an expert for tax questions is also included with TurboTax Live Full Service and available through December 31, 2025. If you use TurboTax Live, Intuit will assign you a tax expert based on availability. Tax expert availability may be limited. Some tax topics or situations may not be included as part of this service, which shall be determined at the tax expert’s sole discretion. The ability to retain the same expert preparer in subsequent years will be based on an expert’s choice to continue employment with Intuit and their availability at the times you decide to prepare your return(s). Administrative services may be provided by assistants to the tax expert. On-screen help is available on a desktop, laptop or the TurboTax mobile app. For the TurboTax Live Assisted product: If your return requires a significant level of tax advice or actual preparation, the tax expert may be required to sign as the preparer at which point they will assume primary responsibility for the preparation of your return. For the TurboTax Live Full Service product: Hand off tax preparation by uploading your tax documents, getting matched with an expert, and meeting with an expert in real time. The tax expert will sign your return as a preparer.

7 Available with select products. See pricing on Intuit TurboTax.