Image: Multiplier-CKXTT-Digital

Image: Multiplier-CKXTT-DigitalFree tax filing.

Can you really file taxes for free on Credit Karma? Yes! Nearly 37% of filers qualify. Simple Form 1040 returns only. (No schedules, except for Earned Income & Child Tax Credits, student loan interest, and Schedule 1-A.)1

Image: Desktop_Hero copy

Image: Desktop_Hero copy Image: Desktop_Expert

Image: Desktop_ExpertNew tax laws. More savings.

- Filers could see an up to $1,000 refund increase or lower balance due on average for TY25, based on recent tax law changes.2

- TurboTax Experts can navigate tax laws for you and make sure you get the benefits you qualify for, like new deductions for overtime and qualified tips.

Ready to rule tax season?

Image: Desktop_Illo_Calendar

Image: Desktop_Illo_CalendarYour refund, up to 5 days early

Deposit your federal refund into your own bank account for a fee.4 Or, pay no additional fee when you deposit it into a Credit Karma MoneyTM Spend account.5

You may be able to receive your federal refund early through your bank, credit union or other financial institution. Terms, fees, and delivery dates may vary. Check with your financial institution for details. Up to 5-day early program may change or discontinue at any time.

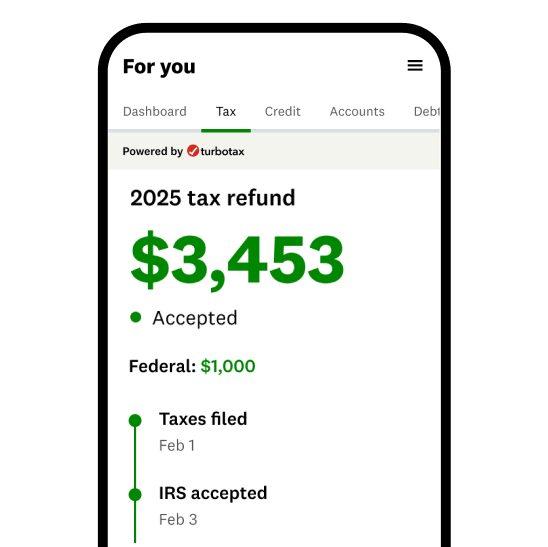

Image: Desktop_Illo_Track

Image: Desktop_Illo_TrackTrack your refund

Monitor and track the status of your refund, from IRS acceptance to delivery date. Using a fast money option? Track that, too!

Get your biggest possible refund, then make it go further.

- TurboTax finds every credit and deduction you’re eligible for, so you get your maximum refund guaranteed (or your money back).6

- Just snap a pic of your W-2 and upload it on the Credit Karma app. We’ll prefill some of your info to give you a head start on your taxes.

- Then, get personalized recommendations on how you can use your tax refund to build financial progress.

Image: Desktop_Refund Tracker UI

Image: Desktop_Refund Tracker UIEditorial Note: Intuit Credit Karma receives compensation from third-party advertisers, but that doesn’t affect our editors’ opinions. Our third-party advertisers don’t review, approve or endorse our editorial content. Information about financial products not offered on Credit Karma is collected independently. Our content is accurate to the best of our knowledge when posted.

Updated February 26, 2026

This date may not reflect recent changes in individual terms.

Tax FAQs: Editors’ answers

Credit Karma and TurboTax work together to simplify your tax filing. Both are part of parent company Intuit, and their partnership can help you file taxes directly in the Credit Karma app. Here are some notable features.

- Prefilled tax documents: You’ll get a head start filing since information from your Credit Karma account can be used to prefill your tax documents.

- Special offers: TurboTax offers multiple levels of service — from free filing for simple returns to full-service support with a tax expert — including options for new filers and people who prefer working with a local expert.

- Early refund access: Get your refund up to five days sooner by having it deposited into a Credit Karma Money™ Spend account, or apply for a TurboTax Refund Advance — a no-cost loan of up to $4,000.

- Track your refund: When you share your data, you’ll be able to follow the progress of both your federal and state refunds right inside Credit Karma using its Refund Tracker.

Most people who e-file and choose direct deposit see their refund within 21 days of the IRS accepting their return, though that timeline can be longer in certain instances.

If you’d like access to your money sooner, TurboTax and Credit Karma offer some options.

- Early refund access: Credit Karma members can receive their tax refund up to five days early by depositing it into a Credit Karma Money™ Spend account — regardless of who prepares the return. But this perk can’t be combined with other options: If you use your federal refund to pay TurboTax fees or take advantage of a TurboTax Refund Advance, you won’t be eligible for early refund access through Credit Karma.

- Refund Advance: Eligible TurboTax e-filers can apply for a short-term, no-cost Refund Advance loan, issued by WebBank. If approved, you can get up to $4,000 deposited into your free Credit Karma Money™ Spend account — often within minutes of IRS acceptance. Refund Advance may not be available for all tax filers everywhere. You’ll want to check out the full terms and conditions before you apply.

Your refund is the difference between what you’ve already paid in taxes and what you actually owe. If you’ve paid more than your total tax bill, you’ll get money back. If you’ve paid less, you’ll owe the IRS when you file.

If you gather your basic financial documents like paystubs or W-2s and 1099s, you can use the Turbotax Tax Calculator to get a personalized refund estimate.

If your estimate shows that you’ll owe a large amount or that you’re getting a big refund, you may want to adjust your W-4 withholding.

Several provisions in the new tax law signed in 2025 could affect the tax return you file for the 2025 tax year. Others changes won’t take effect until 2026 and beyond.

The bill also permanently extended several provisions from the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, including lower individual income tax rates, a higher standard deduction and the elimination of personal and dependent exemptions.

Temporary breaks for workers and seniors (2025–2028)

- Tip income deduction: Eligible workers can deduct up to $25,000 in reported tips, though this benefit starts to phase out at a modified adjusted gross income of $150,000 for single filers and $300,000 for married couples filing jointly.

- Overtime pay deduction: Eligible workers can deduct up to $12,500 in overtime pay, or up to $25,000 if married filing jointly. The deduction phases out once modified adjusted gross income exceeds $150,000 for single filers and $300,000 for joint filers.

- Senior deduction: Eligible taxpayers age 65 and older can claim an extra $6,000 deduction, or $12,000 for married couples where both spouses qualify. This benefit phases out when modified adjusted gross income exceeds $75,000 for single filers or $150,000 for joint filers.

Other notable changes for the 2025 tax year include an increase of the Child Tax Credit to $2,200 and an increase to the state and local tax, or SALT, deduction cap from $10,000 to $40,000.

Having everything ready before you file helps you prepare an accurate return, claim deductions or credits and avoid delays. You can use Credit Karma’s tax document checklist to make sure you’ve got what you need.

Here are the main categories and some of the details to keep in mind.

Personal information

- Social Security numbers (or ITINs) for you, your spouse and dependents

- Last year’s tax return for your adjusted gross income (AGI) and PIN if you e-filed

- Bank account and routing numbers for direct deposit or payments

Income forms

- W-2s from all employers

- 1099s for freelance work, investments, unemployment, retirement distributions or Social Security

- Form 1095-A if you purchased marketplace health insurance

Deductions and credits

- Records of childcare expenses, mortgage interest, property taxes and charitable donations

- Medical bills, retirement contributions or, if you’re a student or teacher, tuition receipts if you plan to claim them

Self-employment and side gigs

- Payment records from apps or banks

- Receipts, invoices and mileage logs for business expenses

- Proof of estimated tax payments

You may be able to file taxes for free using programs like IRS Free File, Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA), Tax Counseling for the Elderly (TCE) and MilTax, or by using free versions of commercial software like Credit Karma powered by TurboTax. These options are available if you meet certain eligibility requirements. And keep in mind to confirm whether a free state filing is included before you start.

1 TurboTax Free Edition ($0 Federal + $0 State + $0 To File) is available for those filing simple Form 1040 returns only (no forms or schedules except as needed to claim the Earned Income Tax Credit, Child Tax Credit, student loan interest, and Schedule 1-A). More details are available here. Roughly 37% of taxpayers qualify. Offer may change or end at any time without notice.

2 According to a recent study from Piper Sandler

+ If you expect to receive a federal refund of $500 or more, you could be eligible for a TurboTax Refund Advance loan. TurboTax Refund Advance loans are issued by WebBank, which is not affiliated with MVB Bank, Inc., Member FDIC. TurboTax Refund Advance is a loan based upon your anticipated refund and is not the refund itself. 0% APR and $0 loan fees. Availability of the TurboTax Refund Advance is subject to satisfaction of identity verification, certain security requirements, eligibility criteria, and underwriting standards. This TurboTax Refund Advance offer expires on April 15, 2026, or the date that available funds have been exhausted, whichever comes first. Offer, eligibility, and availability subject to change without further notice.

3 Acceptance times vary. Most customers receive funds within 5 minutes of acceptance.

4 Money movement services are provided by Intuit Payments Inc., licensed as a Money Transmitter by the New York State Department of Financial Services. For more information about Intuit Payments’ money transmission licenses, please visit https://www.intuit.com/legal/licenses/payment-licenses/.

Up to 5 Days Early to Your Bank Account: Personal taxes only. Your federal tax refund will be deposited to your selected bank account up to 5 days before the refund settlement date provided by the IRS (the date your refund would have arrived if sent from the IRS directly). The receipt of your refund up to 5 Days Early is subject to IRS submitting refund information to us at least 5 days before the refund settlement date. IRS does not always provide refund settlement information early. You will not be eligible to receive your refund up to 5 Days Early if (1) you take a Refund Advance loan, (2) IRS delays payment of your refund, or (3) your bank’s policies do not allow for same-day payment processing. Up to 5 Days Early fee will be deducted directly from your refund prior to being deposited to your bank account. If your refund cannot be delivered at least 1 day early, you will not be charged the Up to 5 Days Early fee. Up to 5 Days Early program may change or be discontinued at any time.

You may be able to receive your federal refund early through your bank, credit union or other financial institution. Terms, fees, and delivery dates may vary. Check with your financial institution for details.

4 Up to 5 Days Early to a Credit Karma Money™ Account: To be eligible, you don’t need to file your taxes with a particular tax prep service. However, you will not be eligible if you choose to pay your tax preparation fee using your federal or state tax refund or choose to take a TurboTax Refund Advance loan. 5-day early program may change or discontinue at any time. Up to 5 days early access to your federal tax refund is compared to standard tax refund electronic deposit and is dependent on and subject to IRS submitting refund information to the bank before release date. IRS may not submit refund information early.

Banking services provided by MVB Bank, Inc., Member FDIC. Credit Karma is not a bank.

5 If you get a larger refund or smaller tax due from another tax preparation method by filing an amended return, we’ll refund the applicable TurboTax federal and/or state purchase price paid. (TurboTax Free Edition customers are entitled to payment of $30.) This guarantee is good for the lifetime of your individual tax return, which Intuit defines as seven years from the date you filed it with TurboTax, or until December 15, 2026 for your 2025 business tax return. Additional terms and limitations apply. See Terms of Service for details.